DDW 2024: Therapeutics for Refractory GERD

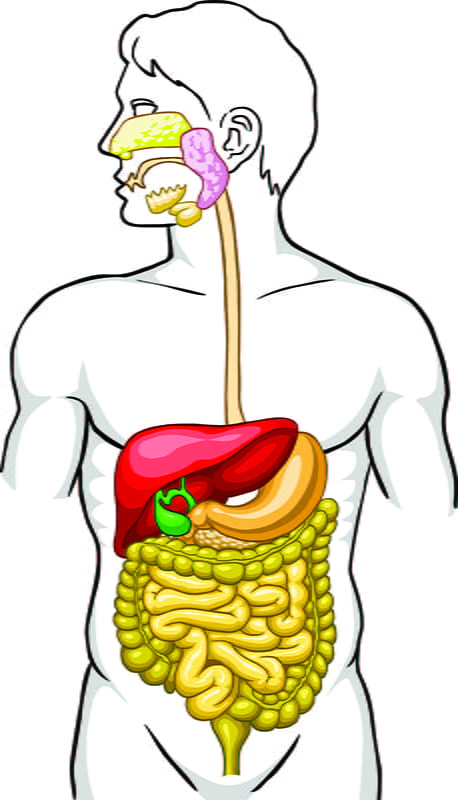

The session focuses on understanding the anti-reflux barrier & GERD spectrum. Further, it encompasses strategies to close the junction, the underlying mechanisms, and the patient-specific factors influencing non-medical therapy selection and overall medical and surgical endoscopic interventions. Along with traditional endoscopy, assessments like hiatal hernia length and esophagitis grade, evaluating the anti-reflux barrier, such as the Hill grade or AFS grade, in retroflex position is becoming increasingly important in GERD. Describing the presence of Barrett's oesophagus and performing pH testing to confirm GERD are essential before considering interventions; however, they are not needed in severe esophagitis or long Barrett's. Manometry is crucial for surgical planning and assessing motility in patients with dysphagia, as suspected gastroparesis may impact treatment decisions, potentially necessitating pyloroplasty or altering the treatment plan. Anatomic evaluation, particularly assessing the Hill grade, is crucial in endoscopy for GERD patients. This involves fully insufflating the stomach for 30 seconds and observing the valve's behaviour, identifying whether it thins out, intermittently opens, or remains open with a wide defect. Furthermore, in GERD, if the patient has the early disease but normally endoscopy with no hernia, however after manoeuvring, the opening is observed, thus suggesting that this is Hill Grade 1 or 2, with lower soft sphincter relaxations and mostly upright reflux and non-erosive reflux disease. As the severity of the defect in the junction barrier increases, patients may develop small hernias, categorized as Hill Grade 3. This can lead to upright reflux in supine positions, necessitating consideration of alternative interventions if medical therapy fails. In cases of large hernias or para-esophageal hernias, surgical intervention becomes the clear choice after unsuccessful medical management.

Non-medical should be considered for patients with pH-proven GERD who have refractory symptoms despite maximal medication, including those with refractory regurgitation or PPI-responsive heartburn. Patients with complications such as refractory esophagitis, LA grade C/D esophagitis, Barrett's oesophagus with large hernias (before EET) or PPI intolerance (e.g., diarrhoea, constipation). Additionally, adverse PPI events warrant consideration for alternative therapies. Factors to consider for non-medical treatment of GERD include consideration of age, particularly in young patients, where the choice between laparoscopic hernia repair and long-term PPI use must be carefully weighed. The junction anatomy, as indicated by Hill grade, informs the options for barrier therapy. Understanding the reflux phenotype, whether regurgitation, non-erosive reflux disease, or high-volume reflux, guides treatment decisions. Patient descriptions of symptoms, such as nighttime choking despite medication and lifestyle modifications, may indicate the need for intervention, including barrier therapy. Motility assessment helps determine the suitability of complete or partial fundoplication. Additionally, understanding patient preferences regarding surgery or medication is essential. For morbidly obese patients with refractory GERD, many traditional treatments are contraindicated. Ideal treatment often involves bariatric surgery, such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. This procedure addresses GERD by excluding acid-producing cells and minimizing bile reflux. Traditional therapies like laparoscopic hernia repair + NISSEN may have increased failure rates and can exacerbate GERD in obese patients. Despite patient reluctance, discussing bariatric options is crucial for effective management.

Barrier therapies address the mechanisms contributing to breakdowns, such as the right crus diaphragm, the flap valve (including the angle of His), and gastric sling fibres. Surgical interventions directly target these defects, whereas endoscopic interventions may not always address them effectively. When intervening to address the anti-reflux barrier, surgeons typically perform procedures to reduce hiatal hernia, repair the crural defect, and strengthen the lower oesophageal sphincter. They aim to reconstruct the dysfunctional flap valve to restore its function. The two main surgical fundoplications are the full Nissen fundoplication, which provides a 3600 posterior wrap, primarily for patients with normal or slightly abnormal oesophageal motility, and the partial fundoplication (Toupet), which provides a 2700 posterior wrap, typically for those with dysphagia or ineffective motility observed by manometry. Laparoscopic Nissens are considered the gold standard and effectively reduce reliance on PPIs, normalizing pH levels. However, they can lead to complications such as gas bloat, dysphagia, and flatulence, with some patients needing to resume PPIs within five years and potentially requiring redo surgery in their lifetime. Failure rates are significant, particularly for younger patients facing lifelong considerations. The FDA-approved LINX procedure involves augmenting the LES with a ring of magnets, increasing pressure while allowing food and liquid passage. However, it was unsuitable for patients with metal allergies and decreased oesophageal motility. Initially studied over 5 years ago, the LYNX procedure showed 64% achieving pH normalization or reduction but notable improvements in symptoms and reduced PPI usage. However, complications like gas bloat, dysphagia, and device erosions were observed. In the recent Caliber trial, LYNX MSA's efficacy in treating medication refractory regurgitation-predominant GERD, the conservative patient group with small hernias and no esophagitis were included, significant improvements were noted, such as symptom relief, 89% pH normalization, and reduced PPI dependency. These findings underscore the potential of LYNX MSA as a durable alternative surgical therapy for select patients. The ACG guidelines suggest MSA or laparoscopic fundoplication for patients experiencing regurgitation after failed medical management, with multi-society guidelines also typically saying MSA is better in patients who failed PPI treatment; however, recent multi-society guidelines suggesting an equivalence between the two based on expert opinion. Current Endoscopic GERD therapies have evolved and include therapies such as augmenting the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) such as Stretta, CLEAR (cardia ligation endoscopic anti-reflux), ARMS (anti-reflux mucosectomy), ARMA (anti-reflux mucosal ablation), RAP (resection + plication), GERD-X (Endoscopic full-thickness plication). Therapies that reduce small hernias and augment the lower soft sphincter include TIF (transoral incisionless fundoplication).

TIF include two types: TIF (transoral incisionless fundoplication) — Esophyx (Endogastric Solutions, USA) and TIF - MUSE (Medigus Ultrasonic Endostapler, Israel). TIF 2.0 with Esophyx Z+ device: HH 1-2 cm, Hill 1-2 effectively controls GERD symptoms, especially in patients with small hiatal hernias or no hernia and a Hill grade 1-2 defect. TIF involves repairing small hernias and creating a 270 to 300-degree valve, similar to a partial fundoplication. While TIF improves symptoms and patient satisfaction, its efficacy in getting patients off PPIs or normalizing acid reflux varies. However, real-world data from TIF registries show positive outcomes across different levels of practitioner experience and further help 80% of the population to avoid PPI & 72 % normalization of their acid exposure time over four days. It offers a physiologic valve, high-quality satisfaction with minimal gas bloat or dysphagia, standardized procedure, and potential for repeatability. TIF can serve as a bridge for failed Nissens, providing an outpatient, endoscopic alternative to repeat surgery. However, the disadvantages of the procedure include the requirement of 2 operators, limited long-term data and adoption limited by availability, training, cost and insurance coverage. As per recent multi-society guidelines, adult patients with GERD may benefit from TIF 2.0 over continued PPI. AGA clinical practice update suggests that transoral incisionless fundoplication is an effective endoscopic option for carefully selected patients with proven GERD. ACG guidelines suggest considering TIF for selected patients with regurgitation-predominant symptoms and without severe esophagitis, provided they meet anatomical criteria. The forthcoming ASG guidelines are expected to align, favouring barrier therapies like TIF over PPIs for GERD patients with predominant regurgitation who seek alternatives to surgery and long-term PPI use.

Concomitant TIF with hernia repair, known as C-TIF, offers a comprehensive approach for patients with larger hernias and higher HlLL grades. This procedure combines hernia reduction, crural defect repair, and TIF in a single setting. An ongoing randomized trial aims to compare its efficacy with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Other endoscopic options include Endoscopic Full Thickness Plication (EFTP) GERD-X (G-SURG, Germany) that placates the junction with braided sutures & titanium, Cardia Ligation Endoscopic Anti-Reflux (CLEAR) that binds the four sections of the cardia to induce a controlled kind of stricture at the junction, Radiofrequency ablation, or Stretta, involves applying low-power radio heat to the muscle while cooling the mucosa to enhance the gastroesophageal junction barrier. It may benefit patients with non-erosive GERD or post-sleeve gastrectomy GERD, but further study is needed. Conflicting data exists regarding its efficacy, with some studies suggesting no significant difference from sham or control. While some multi-society guidelines suggest it may be superior to PPIs, the ACG does not currently recommend its use due to inconclusive evidence, favouring fundoplication. The ASG guidelines suggest offering Stretta as an option when other techniques are unavailable, although its efficacy is uncertain for patients with early-stage disease. Another method, anti-reflux mucosectomy (ARMS), involves resecting part of the cardia and is currently being tested. When deciding on treatments, factors include quality of life improvements, acid pH normalization, technical ease, cost-effectiveness, and patient acceptance. Most endoscopic therapies are quick, the quickest one being the bind-ligation technique, with high clinical success rates for TIF and ARMA. TIF also shows the highest rates of PPI discontinuation and acid exposure normalization. Costs vary, with ARMA or CLEAR being the least expensive and highest among the other device-related treatments. Dysphagia can occur with treatments like Stretta, mucosal resection, and ablation, and technical difficulty varies, with a learning curve for trans-esophageal plication techniques.

In summary, GERD patients are refractory to medical management. It is advised to look at early disease with small or no hernias. For advanced cases, surgery is necessary as medications and endoscopic treatments are less effective. Barriers to adoption include therapy challenges, lack of randomized trials, inconsistent insurance coverage, training for new techniques, collaboration between surgeons and GIs and patient preferences. Endotherapy for GERD is evolving as a bridge between PPIs and surgery. Success depends on proper patient selection, a personalized step-up approach, and shared decision-making. More patient-centred comparative research is needed to advance the field.

Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2024, May 18-21, 2024, Washington, D.C.