Antiretroviral-based Prevention Strategies in HIV

Introduction

The UNAIDS 2016, Global AIDS Update, reported that the global coverage of ART has reached 46%. Eastern and Southern Africa experienced the largest gains, where coverage increased from 24% in 2010 to 54% in 20151.

As of 2015, the annual number of new infection has remained stable at 1.9 million. However, in 2017, UNAIDS estimates showed a slightly different trend. Between 2010 and 2015 new infections declined by an estimated 8% and between 2010-2016 by 11%. Eastern and Southern Africa had an estimated 18% decline in adult HIV infections since 2010. Despite this remarkable decrease in new HIV infections (across all ages), the pace of decline in new HIV infections is far too slow to reach the Fast-Track Target agreed upon by the United Nations General Assembly in 2016. This is represented in Figure 1 below.2

Currently, 19.5 million people are receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART).2 ART has played a major role in curbing the morbidity and mortality rates in the HIV-infected population.

Even with impressive scale-up of ART and a decline in incidence, HIV continues to remain one of the crucial challenges in many parts of the world. HIV is the leading cause of death in Sub-Saharan Africa, among women of reproductive age. It is the third leading cause of death in low-income countries, and the sixth leading cause of death worldwide.3

Thus, preventing new HIV infections remains one of the world’s most important health priorities. Along with the existing prevention methods like post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) and use of condoms, newer preventive strategies are gaining attention. These include use of newer technologies (microbicides, multipurpose preventive technologies (MPTs), circumcision techniques, etc.), novel applications of existing antiretroviral drugs for treatment (e.g. oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and, ‘treatment as prevention (TasP)’) to prevent new HIV infections. New bio-medical interventions have also shown to be effective in preventing HIV transmission.4

Antiretrovirals as Prevention

In addition to the proven role of antiretrovirals (ARVs) in treatment, they also play an important role in prevention. ARVs can be used to prevent HIV transmission in one of the following ways 5

- Before exposure

- as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

- as treatment of infected people for secondary prevention, such as Treatment as Prevention (TasP)

- as preventing mother-to-child transmission strategies (PMTCT)

- After exposure

- as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (Prep)

Introduction

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection is a strategy where ARVs are administered to HIV-negative individuals who are at a high risk of HIV acquisition to decrease the risk of establishment of HIV infection.6 Different dosing strategies have been studied for PrEP use among high–risk HIV-uninfected populations. The dosing regimens are as follows:

- Daily dosing – one tablet once daily

- Event-based dosing – two tablets 2 to 24 hours prior to the event + one tablet 24 hours after the event + one tablet 48 hours after the event.

- Time-based dosing - Twice weekly with a post sex dose.

The US FDA has currently approved only the daily dosing regimen for PrEP use while France is the sole country to approve the event–based dosing regimen but only in MSMs.

In the first quarter of 2017 more than 120,000 people were using PrEP in the US. The average age of people starting PrEP was approximately 38 years for men and 35 years for women. The growth for PrEP use has been slow and steady in the US with the stabilization phase being reached between the first and third quarter of 2015 (at <1% increase per quarter).7

Clinical evidence across different high risk populations have shown that when PrEP is taken daily with a high level of adherence it reduces the risk of acquiring HIV by more than 90%.

Country Updates8

In India, Cipla has received Regulatory approval for the use of Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) for PrEP. Other countries that have approved (TDF/FTC) for PrEP as of November 2017 are as follows

|

USA |

Peru |

Lesotho |

|

France |

South Africa |

Malawi |

|

Canada |

Australia |

Namibia |

|

Kenya |

Israel |

Thailand |

|

Norway |

Eurpoean Union |

Taiwan |

Recommended Regimen for PrEP (WHO and CDC)

The fixed-dose combination of TDF/FTC as a single daily dose is currently the only US FDA approved combination for PrEP in healthy adults (HIV-uninfected) at risk of acquiring HIV infection.

Dosage: TDF/FTC (300 mg/200 mg) once a day.

WHO Recommendations9

- The WHO recommends oral PrEP for preventing the acquisition of HIV infection as follows:

- ‘Oral PrEP containing TDF should be offered as an additional prevention choice for people at substantial risk of HIV infection as part of combination HIV prevention approaches’.

WHO has also defined the term ‘Substantial risk’ as follows

Substantial risk of HIV infection is provisionally defined as HIV incidence greater than 3 per 100 person–years in the absence of PrEP. HIV incidence greater than 3 per 100 person–years has been identified among some groups of men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women (TGW) in many settings and heterosexual men and women who have sexual partners with undiagnosed or untreated HIV infection. Individual risk varies within groups at substantial risk depending on individual behaviour and the characteristics of sexual partners.

WHO Implementation Tool for PrEP of HIV Infection9

The WHO recently launched its implementation tool for PrEP. It has 11 modules to support the implementation of PrEP among a range of populations in different settings. They are listed in brief below.

Module 1: Clinical

It describes the important considerations to be taken in to account when starting PrEP in an individual and monitoring PrEP use among them. This module tries to provide a summary of relevant information for clinicians, including physicians, nurses and clinical officers, who are providing PrEP in clinical settings.

Module 2: Community Educators and Advocates

Community educators and advocates are required to increase awareness about PrEP in their communities for PrEP services to reach populations in an effective and acceptable way,. This module provides up-to-date information on PrEP that should be considered in community-led activities. It would increase knowledge about PrEP and create demand and access.

Module 3: Counsellors

This module would enable staff who counsel people as they consider PrEP or start taking PrEP and support them in addressing issues around coping with side effects and adherence strategies. Counsellors to PrEP users may be lay, peer or professional counsellors and healthcare workers.

Module 4: Leaders

This module aims to update and inform leaders and decision-makers about PrEP. It provides information on the benefits and limitations of PrEP so that they can consider how PrEP could be most effectively implemented in their own settings. It also contains a series of frequently asked questions about PrEP, with related answers.

Module 5: Monitoring and Evaluation

This module is meant for people responsible for monitoring PrEP programmes at the national and site levels. It provides information on how to monitor PrEP for safety and effectiveness, suggesting core and additional indicators for site-level, national and global reporting.

Module 6: Pharmacists

This module is for pharmacists and people working in pharmacies under a pharmacist’s supervision. It provides information on the medicines used in PrEP, including the optimal storage conditions. It also gives suggestions for how pharmacists and pharmacy staff can monitor PrEP adherence and support PrEP users to take their medication regularly.

Module 7: Regulatory Officials

National authorities in charge of authorizing the manufacturing, importation, marketing and/or control of ARV medicines used for HIV prevention can get all the required information from this module. It provides information on the safety and efficacy of PrEP medicines.

Module 8: Site Planning

This module is for people involved in organizing PrEP services at specific sites. It outlines the steps to be taken in planning a PrEP service and gives suggestions for personnel, infrastructure and commodities that could be considered when implementing PrEP.

Module 9: Strategic Planning

As WHO recommends offering PrEP to people at substantial HIV risk, this module offers public health guidance for policy-makers on how to prioritize services, in order to reach those who could benefit most from PrEP, and in which settings PrEP services could be most cost-effective.

Module 10: Testing Providers

Those responsible for providing testing services at PrEP sites and associated laboratories can get all the essential information from this module. It offers guidance in selecting relevant testing services, including appropriate screening of individuals before PrEP is initiated and monitoring while they are taking PrEP. Information is provided on testing for HIV, creatinine, hepatitis B and C virus, pregnancy and STIs.

Module 11: Prep Users

This module provides information for people who are interested in taking PrEP to reduce their risk of acquiring HIV and people who are already taking PrEP – to support them in their choice and use of PrEP. This module gives ideas for countries and organizations implementing PrEP to help them develop their own tools.

CDC Recommendations10

The CDC guidelines recommends the use daily oral antiretroviral PrEP to reduce the risk of acquiring HIV infection in adults. TDF/FTC is recommended as one of the prevention options for the following adult populations who are at substantial risk of HIV acquisition:

- Sexually-active adult MSM

- Heterosexually active men and women

- Injection drug users (IDU)

- Heterosexually-active women and men whose partners are known to have HIV infection (i.e., HIV-serodiscordant couples) as one of several options to protect the uninfected partner during conception and pregnancy so that an informed decision can be made in awareness of what is known and unknown about the benefits and risks of PrEP for the mother and the fetus.

Clinicians Initiating the Provision of PrEP10

Clinicians initiating PrEP should do the following

- Prescribe medication regimens that are proven safe and effective for uninfected persons who meet recommended criteria to reduce their risk of HIV acquisition.

- Educate patients about the medications and the regimen to maximize their safe use.

- Provide support for medication-adherence to help patients achieve and maintain protective levels of medication in their bodies.

- Provide HIV risk-reduction support and prevention services or service referrals to help patients minimize their exposure to HIV.

- Provide effective contraception to women who are taking PrEP and who do not wish to become pregnant.

- Monitor patients to detect HIV infection, medication toxicities, and levels of risk behaviour in order to make indicated changes in strategies to support the patients’ long-term health.

These goals have been framed by the CDC to reduce the HIV-associated morbidity, mortality and costs to individuals and society.

Clinical Follow-up and Monitoring10

Once PrEP is initiated, patients should return for follow-up approximately every 3 months. Clinicians may wish to see patients more frequently at the beginning of PrEP (e.g., 1 month after initiation), to assess and confirm HIV-negative test status, assess for early side effects, discuss any difficulties with medication adherence, and answer questions.

All patients receiving PrEP should be seen as follows

At least every 3 months to

- Repeat HIV testing and assess for signs or symptoms of acute infection to document that patients are still HIV negative.

- Repeat pregnancy testing for women who may become pregnant.

- Provide a prescription or refill authorization of daily TDF/FTC for no more than 90 days (until the next HIV test).

- Assess side effects, adherence, and HIV acquisition risk behaviours.

- Provide support for medication adherence and risk-reduction behaviours.

- Respond to new questions and provide any new information about PrEP use.

At least every 6 months to

- Monitor eCrCl

- If other threats to renal safety are present (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), renal function may require more frequent monitoring or may need to include additional tests (e.g., urinalysis for proteinuria).

- A rise in serum creatinine is not a reason to withhold treatment if eCrCl remains ≥60 ml/min.

- If eCrCl is declining steadily (but still ≥60 ml/min), consultation with a nephrologist or other evaluation of possible threats to renal health may be indicated.

- Conduct STI testing recommended for sexually active adolescents and adults (i.e., syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia).

At least every 12 months to

- Evaluate the need to continue PrEP as a component of HIV prevention.

Medications Not To Be Used10

Only daily oral dose of TDF/FTC is approved, daily dose of TDF alone as an alternative only for IDU and heterosexually active adults could be used. The following needs to be kept in mind while prescribing PrEP therapy:

- Do not use other antiretroviral medications (e.g., 3TC), either in place of, or in addition to, TDF/FTC or TDF.

- Do not use other than daily dosing (e.g., intermittent, episodic [pre/post sex only], or other discontinuous dosing).

- Do not provide PrEP as expedited partner therapy (i.e., do not prescribe for an uninfected person not in your care).

Side Effects10

Patients taking PrEP should be informed of side effects among HIV-uninfected participants in clinical trials. In these trials, side effects were uncommon and usually resolved within the first month of taking PrEP (‘start-up syndrome’).

Clinicians should discuss the use of over-the-counter medications for headache, nausea, and flatulence should they occur.

Patients should also be counselled about signs or symptoms that indicate a need for urgent evaluation (e.g. those suggesting possible acute renal injury or acute HIV infection).

Discontinuing PrEP10

- Patients may discontinue PrEP medication for several reasons like:

- Personal choice

- Changed life situations resulting in lowered risk of HIV acquisition

- Intolerable toxicities

- Chronic non-adherence to the prescribed dosing regimen despite efforts to improve daily pill-taking

- Acquisition of HIV infection

- Upon discontinuation for any reason, the following should be documented in the health record:

- HIV status at the time of discontinuation

- Reason for PrEP discontinuation

- Recent medication adherence and reported sexual risk behavior

Other Considerations

Women who become pregnant or breastfeed while taking PrEP medication10

PrEP use periconception and during pregnancy by the uninfected partner may offer an additional tool to reduce the risk of sexual HIV acquisition. Both the FDA labeling information and the perinatal ARV treatment guidelines permit this use. Providers should discuss available information about potential risks and benefits of beginning or continuing PrEP during pregnancy so that an informed decision can be made.

Patients with chronic active HBV infection10

- TDF and FTC are each active against both HIV infection and HBV infection and, thus, may prevent the development of significant liver disease by suppressing the replication of HBV.

- Patients should be tested for HBV DNA by the use of a quantitative assay to determine the level of HBV replication before PrEP is prescribed and every 6–12 months while taking PrEP.

Patients with chronic renal failure10

HIV-uninfected patients with chronic renal failure, as evidenced by an eCrCl of <60 ml/min, should not take PrEP because the safety of TDF/FTC for such persons was not evaluated in the clinical trials.

Adolescent Minors10

Clinicians considering providing PrEP to a person under the age of legal adulthood (a minor):

- Should be aware of local laws, regulations, and policies

- Lack of data on safety and effectiveness of PrEP taken by persons under 18 years of age

- Possibility of bone or other toxicities among youth who are still growing; and

- Safety evidence available when TDF/FTC is used in treatment regimens for HIV-infected youth

Important to counsel about10

Medication adherence is critical to achieving the maximum prevention benefit and reducing the risk of selecting for a drug-resistant virus if non-adherence leads to HIV acquisition.

Reducing HIV Risk Behaviours10

The adoption and the maintenance of safer behaviors (sexual, injection, and other substance abuse) are critical for the lifelong prevention of HIV infection and are important for the clinical management of persons prescribed PrEP.

Data from Clinical Trials

Several clinical trials have demonstrated safety and a substantial reduction in the rate of HIV acquisition with the use of TDF/FTC or TDF as PrEP in the high-risk populations.10 The following table provides a summary of the efficacy trials done with a once-daily dosing regimen of PrEP in various high-risk populations.

|

Daily dosing Regimen |

|||

|

Study (participants) |

Design |

Outcomes |

Conclusion |

|

iPrEx Study11 (Men who have sex with men (MSM)) |

Phase 3 TDF/FTC OD (n=1,251) and Placebo (n=1,248) |

100 became infected during follow-up 36 in the TDF/FTC group, indicating a 44% reduction in the incidence of HIV (P=0.005) |

Oral TDF/FTC provided protection against the acquisition of HIV infection among HIV-seronegative men or transgender women who have sex with men. Nausea was reported more frequently during the first 4 weeks in the TDF/FTC group. |

|

Partners PrEP12 (Heterosexual Men and women) |

Phase 3 TDF OD (n=1,584) TDF/FTC OD (n=1,579) and Placebo (n=1,584) |

82 HIV-1 infections occurred in seronegative participants: 17 in the TDF group 13 in the TDF/FTC group Indicating a relative reduction of -67% in the incidence of HIV-1 with TDF -75% in the incidence of HIV-1 with TDF/FTC (P<0.001) |

Oral TDF and TDF/FTC both protect against HIV-1 infection in heterosexual men and women. Rate of serious adverse events was similar across the groups. |

|

TDF213 (Heterosexual Men and women) |

Phase 2 TDF/FTC OD (n=611) Placebo (n=608) |

33 participants who became infected 9 in the TDF/FTC group. The efficacy of TDF/FTC was 62.2% (P=0.03). |

Daily TDF/FTC prophylaxis prevented HIV infection in sexually active heterosexual adults. |

|

Bangkok Tenofovir Study (BTS)14 (Injecting Drug Users) |

Phase 3 TDF OD (n=204) Placebo (n=209) |

50 became infected during follow-up: 17 in the TDF group and 33 in the placebo group, indicating a 48.9% reduction in HIV incidence. (P=0.01) |

Daily oral tenofovir reduced the risk of HIV infection in people who inject drugs. |

|

PROUD study15 (MSM) |

TDF/FTC OD initiated immediately (IMM, n= 276) TDF/FTC OD deferred for 12 months and then followed quarterly (DEF, n=269) |

3 HIV infections in IMM group (1.3/100 PY) and 19 infections in DEF group (8.9/100 PY) Yielding a rate difference of 7.6/100 PY. Indicating a reduction of 86% in HIV incidence (P=0.0002) |

Daily TDF/FTC conferred impressive protection against HIV in the high-risk MSM group. |

|

Newer Segment of High Risk Population Under Clinical Evaluation |

|||

|

Safety and Feasibility of ARV PrEP for Adolescent MSM Aged 15 to 17 Years in the United States16 |

PrEP demonstration project among healthy young MSM aged 15 to 17 years. (n-78). All participants received daily TDF/FTC as PrEP for 48 weeks. |

Over 48 weeks of PrEP use, seroconversion rate was 6.4 per 100 person-years. Tenofovir diphosphate levels consistent with a high degree of anti-HIV protection. |

For the most part, TDF/FTC was well-tolerated in the participants; none of the participants experienced adverse effects on their kidneys or bones. This is a new target population that is being studied. PrEP is not yet approved in this age group. |

PY: Patient-years

Newer Dosing Strategies for PrEP Use among MSM/TG

IPERGAY Study17

Researchers conducted a double blind randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sexual activity-dependent PrEP with TDF-FTC among high-risk MSM in France and Canada. Between February 2012 and October 2014, 414 HIV-negative participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either TDF/FTC or placebo. Participants were told to take a loading dose of two pills of TDF/FTC or placebo with food 2 to 24 hours before sex, followed by a third pill 24 hours after the first drug intake and a fourth pill 24 hours later. In case of multiple successive episodes of sexual intercourse, participants were instructed to take one pill per day until the last sexual intercourse and then to take the two post-exposure pills. All participants received risk-reduction counselling and condoms, and were regularly tested for HIV-1 and HIV -2 and other STIs.

Of the 414 participants, 199 were in the TDF/FTC group and 201 were in the placebo group. Participants were followed for median of 9.3 months. A total of 16 HIV-1 infections occurred during follow-up–2 in the TDF/FTC group and 14 in the placebo group–representing a relative reduction in the incidence of HIV-1 acquisition in the TDF/FTC group of 86% (p<0.002). A median of 15 pills of TDF/FTC or placebo per month (P = 0.57) was taken by the participants. The rates of serious adverse events were similar in the two study groups. Higher rates of gastrointestinal adverse events (14% vs 5%, P = 0.002) and renal adverse events (18% vs. 10%, P = 0.03) were observed in the TDF-FTC group vs the placebo group.

In conclusion, the study researchers reported that among MSM, the use of TDF/FTC before and after sexual activity provided adequate protection against HIV.

HPTN 067/ADAPT Study18

The ADAPT study was a trio of three Phase II randomized, open-label PrEP trials, investigating the feasibility and acceptability of different PrEP regimens among MSM, TGW, and women having sex with men (WSM) in Bangkok (MSM/TGW), Harlem (New York (MSM/TGW)) and Cape Town (WSM).

The trial participants were randomized (1:1:1) to receive one of the following three PrEP regimens: either a daily dose of TDF/FTC (D arm), or a twice-weekly dose of TDF/FTC + an extra dose after sex (T arm), or an event-driven dosing [one dose up to 48 hours before sex, another 2 hours after sex (E arm)]. The participants were followed for 6 months. Adherence and coverage were assessed using electronic monitoring adjusted by self-reported sex and pill-taking behaviour collected in detailed weekly interviews.

Adherence in the above studies was as follows

|

Sites |

Arms |

||

|

D Arm |

T Arm |

E Arm |

|

|

Bangkok |

85% |

79% |

65% |

|

Harlem |

65% |

46% |

41% |

The primary analysis was of the percentage of reported sexual acts that were protected by PrEP, with doses both before and after sex.

- In Bangkok, PrEP coverages were similar in arms D and T (85% vs 84%, p=0.79) and both were greater than in arm E (74%) (p<0.05).

- In Harlem, the daily regimen protected 66% of sexual acts, the twice-weekly regimen protected 47%, and the event-driven regimen protected 52%.

- In Cape Town, the daily regimen protected 75% of sexual acts, the twice-weekly regimen protected 56%, and the event-driven regimen protected 52%.

Also, it was observed that over 90% of participants from Bangkok, in each arm, had detectable drug, with no significant differences between arms. Comparatively, in Harlem and Cape Town, participants were more likely to have detectable drug if they were taking daily PrEP dosing.

There was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of side effects between arms. Gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms (dizziness, headaches, nausea, diarrhoea, etc.) reported were mild and mostly experienced during the first 2 months of taking PrEP. The non-daily regimens required the use of considerably fewer tablets compared with daily dosing, which could make providing PrEP more affordable.

The studies demonstrated the following

- The feasibility of intermittent PrEP, as a, potentially, more cost-effective alternative to daily PrEP, among US Black MSM in Harlem.

- Time-driven dosing regimen was found to offer comparably high PrEP coverage for sex acts among Thai MSM, despite slightly less adherence, while requiring fewer tablets.

- The daily dosing resulted in higher coverage of sex events, higher drug concentrations, and higher adherence among women in Cape Town.

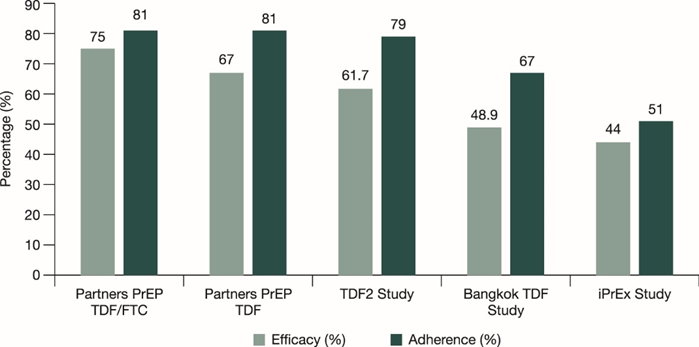

Overview of PrEP adherence and PrEP efficacy in key studies19

US Demo Project20

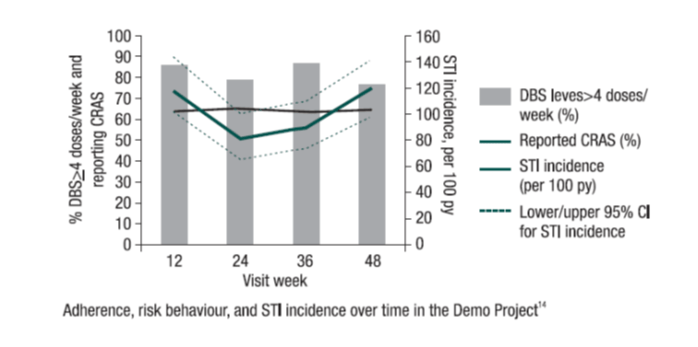

The first US multi-site, open-label Demo Project was conducted to assess PrEP delivery in municipal STD (San Francisco, Miami) and community-health (Washington, DC) clinics.

Investigators enrolled 557 HIV-uninfected MSM/TGW from 9/2012 to 1/2014. They were offered 48 weeks of PrEP. Tenofovir-diphosphate levels were measured in dried blood spots (DBS) in a random sample of participants. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess correlates of adherence. Sexual behaviours, PrEP discontinuations, and HIV/STI incidence were also described.

Among 147 participants with DBS testing, 65% had drug levels consistent with taking ≥4 doses/week at all visits, 3% always had DBS levels <2 doses/week, and 32% had an inconsistent pattern.

Black patients, being self-referred to the PrEP programme, and having a greater number of condomless anal sex (AS) partners were independently associated with DBS ≥4 doses/week (all p<0.05). There was a decline observed in the past 3 months in the number of AS partners, from baseline to week 48 (P<0.0008). Condomless receptive AS (CRAS) reported by two-thirds of the population at baseline was found to be stable during follow-up (p=0.96).

PrEP was discontinued by 20 participants due to low self-perceived HIV risk and 65% of these participants reported CRAS in the prior 3-6 months. The incidence of STI was found to be high; however, it did not increase over time (p=0.87). Overall, 27.5% had early syphilis, GC, or CT at screening, and 38% had ≥1 STI during follow-up;STI incidence was high (47.9, 42.8, and 12.6/100 py for CT, GC, and syphilis) but did not increase over time (p=0.87).

The Demo Project demonstrated high adherence to PrEP among the study population. Also, HIV incidence was low in this cohort at ongoing high sexual risk for HIV. The incidence of STIs was found to be high during PrEP use, thus screening for and treatment of STIs remains important.

Overall Strategy for PrEP Management10

|

|

Men Who Have Sex with Men |

Heterosexual Women and Men |

Injection Drug Users |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Detecting substantial risk of acquiring HIV infection |

HIV-positive sexual partner Recent bacterial STI High number of sex partners History of inconsistent or no condom use Commercial sex work |

HIV-positive sexual partner Recent bacterial STI High number of sex partners History of inconsistent or no condom use Commercial sex work In high-prevalence area or network |

HIV-positive injecting partner Sharing injection equipment Recent drug treatment (but currently injecting) |

|

Clinically eligible |

Documented negative HIV test result before prescribing PrEP No signs/symptoms of acute HIV infection Normal renal function; no contraindicated medications Documented hepatitis B virus infection and vaccination status |

||

|

Prescription |

Daily, continuing, oral doses of TDF/FTC <90-day supply |

||

|

Other services |

Follow-up visits at least every 3 months to provide the following: HIV test, medication adherence counselling, behaviours risk reduction support, side effect assessment, STI symptom assessment At 3 months and every 6 months thereafter, assess renal function Every 6 months, test for bacterial STIs |

||

|

|

Do oral/rectal STI testing |

Assess pregnancy intent Pregnancy test every 3 months |

Access to clean needles/syringes and drug treatment services |

Conclusion

ARV prophylaxis has been very effective in preventing MTCT of HIV and, therefore, there is a great hope that this strategy will prove effective against other routes of HIV transmission. In the absence of an effective vaccine, use of ARV drugs as PrEP might be a reliable intervention to protect high-risk HIV-negative people from infection. Many currently available drugs for treatment also have desirable characteristics and are being analysed for use as PrEP.21

Treatment as Prevention (Tasp)

As people are living longer with HIV, a new demographic – ‘the serodiscordant couple’ – has emerged where one partner is HIV-positive and the other partner is HIV-negative. In these cases, prevention of transmission to the uninfected partner is of utmost importance.

TasP is a term used to describe HIV prevention methods that use ART in HIV-positive persons to decrease the chance of HIV transmission independent of CD4 cell count.22

ART has been effective in reducing the amount of HIV-1 in genital secretions. Because the sexual transmission of HIV-1 from infected persons to their partners is strongly correlated with concentrations of HIV-1 in blood and in the genital tract, it has been hypothesized that ART could reduce sexual transmission of the virus. Several observational studies have reported decreased acquisition of HIV-1 by sexual partners of patients receiving ART.23 The definitive proof for this approach came from the HPTN 052 study, which has been hailed as THE BREAKTHROUGH OF THE YEAR 2011 by Science Magazine.24

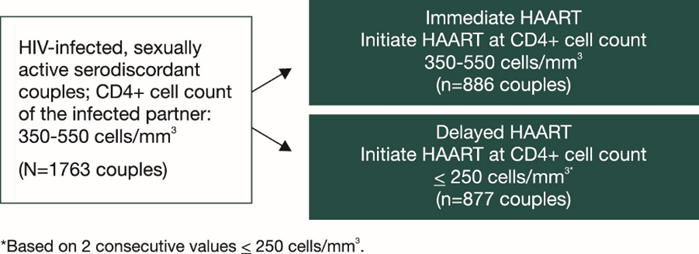

About HPTN 05223,25,26

HPTN 052 was designed to evaluate whether immediate versus delayed use of ART by HIV-infected individuals would reduce transmission of HIV to their HIV-uninfected partners and potentially benefit the HIV-infected individual as well. The study was conducted at 13 sites across Africa, Asia and the Americas.

Couples were required to have had a stable relationship for at least 3 months and not have received any previous ART except for short-term prevention of MTCT of HIV-1.

The study design was as follows:

- Primary endpoint: Virologically linked HIV transmission that was confirmed by genetic analysis.

- Median follow up was 1.7 yrs.

- Primary clinical endpoints: WHO stage 4 events, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), severe bacterial infection and/or death.

- Participants assessed every 3 months.

Key Findings

- Immediate ART in the HIV-infected partner is associated with a 96% reduction in the risk of transmission in serodiscordant couples.

- Total number of HIV-1 transmission events observed were 39, which translates into a 96% reduction in the risk of transmission (p<0.0001).

- Statistical significant reduction in the risk of extrapulmonary TB in the early treatment arm: 17 cases occurred in the deferred arm vs 3 in the early treatment arm (p=0.0013).

In the final outcomes of the HPTN 052 trial, it was observed that after ART was offered to index participants in both study arms, there were two linked infections in the early arm (15 total infections/2,537 py) and 7 linked infections in the delayed arm (17 total infections/2,412 py). This indicates a 93% reduction in the risk of transmission of HIV among serodiscordant couples.

Also, there were only 7 linked infections diagnosed while the index participants were receiving ART: 4 infections diagnosed shortly after the index participant started ART and 3 were diagnosed after ART failure. These outcomes showed that HIV transmission is very unlikely when viral replication is suppressed.

Therefore, the previously reported efficacy of early ART for HIV prevention was sustained for the duration the trial. ART, combined with counselling and provision of condoms provides durable, highly-effective protection from HIV transmission in serodiscordant couples.

In light of the results of HPTN 052, the WHO and many organizations have formulated recommendations regarding the use of ART for treatment and prevention in serodiscordant couples.

|

Guidelines |

Recommendations on TasP |

|

DHHS 201727 |

ART should be offered to patients who are at risk of transmitting HIV to sexual partners |

|

BHIVA 201628 |

The use of ART to reduce transmission risk is a particularly important consideration in serodiscordant heterosexual couples wishing to conceive, and it is recommended that the HIV-positive partner be on fully suppressive ART |

|

EACS 201729 |

Use of ART should also be recommended with any CD4 count in order to reduce sexual transmission |

|

IAS 201630 |

ART is recommended for the treatment of HIV infection and for the prevention of transmission of HIV |

|

WHO 201631,32 |

Initiate ART regardless of WHO clinical stage and CD4 cell count in HIV-positive individual in a serodiscordant partnership (to reduce HIV transmission risk) |

Thus, ART should be an option available to all serodiscordant heterosexual couples as part of a comprehensive combination prevention strategy.

Preventing Mother-To-Child Transmission (PMTCT)

Mother-to-child transmission of HIV can occur either during pregnancy, labour, delivery or breastfeeding. In the absence of any interventions the rate of transmission ranges between 15-45%. This rate can be reduced to levels below 5% with effective interventions.33

Interventions to reduce MTCT: 31

- ART for the mother and baby

- Avoidance of breastfeeding

- Alternatively, exclusive breastfeeding and receive ARV

|

Pregnant and breastfeeding women with HIV |

HIV-exposed infant |

|

|

ART should be initiated in all pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV regardless of WHO clinical stage and at any CD4 cell count and continued lifelong |

Breastfeeding |

Replacement feeding |

|

6 weeks of infant prophylaxis with once daily NVP |

4–6 weeks of infant prophylaxis with once-daily NVP or twice-daily AZT |

|

The combination of TDF + 3TC (or FTC) + EFV (once-daily fixed-dose combination) is recommended as first-line ART in pregnant and breastfeeding women, including pregnant women in the first trimester of pregnancy and in women of childbearing age. The recommendation applies both to lifelong treatment and to ART initiated for PMTCT and then stopped.

In the third quarter of 2011, the Malawi Ministry of Health (MOH) implemented the ‘Option B+’ and showed a significant impact at the end of the third quarter of 2012, which was summarized in a report. Implementation of Option B+ resulted in a 748% increase in the number of pregnant and breastfeeding women starting ART, from 1,257 in the second quarter of 2011 (representing 5% of all new ART initiations) to 10,663 in the third quarter of 2012 (35% of all new ART initiations).34

Between 2011 and 2015, the proportion of women with HIV who were diagnosed went from 49 to 80%, and the proportion who were virally suppressed jumped from 2 to 48%. The percentage of mothers receiving ART to prevent MTCT dramatically increased from 17% in 2009 to 80% in 2015. Approximately 73% of women on Option B+ were still receiving treatment after 12 months and around 71% after 24 months.35

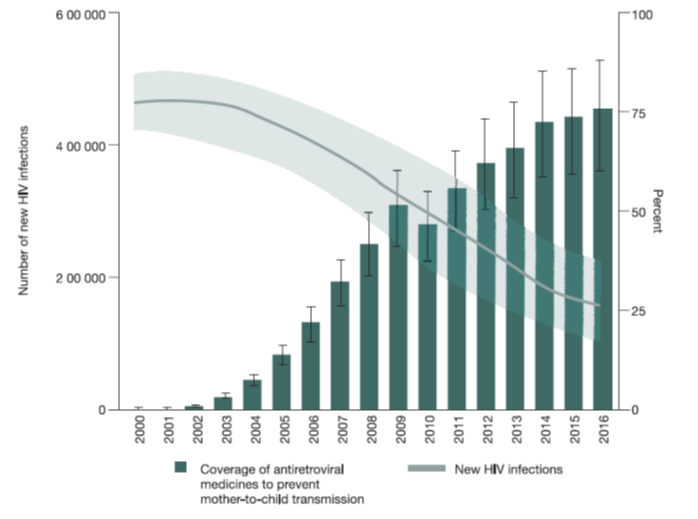

Current Status2

The UNAIDS 2016 fact sheet, reported that 6% of pregnant women living with HIV received ARV medicines to avoid HIV transmission to their newborns. The number of children newly infected with HIV globally in 2014 was reported to be 220,000 which is less than half the number who acquired HIV in 2000. Among children, new infections have declined 47% since 2010. Figure 5 below illustrates the same.

Figure 4: New HIV infections among children (aged 0–14 years) and coverage of Antiretroviral Regimens to prevent mother-to-child transmission, global, 2000–2016

Source: UNAIDS 2017 estimates

Therefore, with the rapid expansion of services and efforts to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission, a massive impact has been seen in preventing transmission to children and, in turn,contributing to global efforts to reduce mortality in children.

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

Preventing exposures to blood and body fluids (i.e. primary prevention) is the most important strategy for preventing acquisition of HIV infection. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is the use of short-term ART to reduce the risk of acquisition of HIV infection following exposure. It is widely available following occupational exposure to HIV and has become increasingly available for non-occupational exposure to HIV.36

The updated WHO 201437 and US Public Health Service 201338 guidelines consist of recommendations for the management of persons who experience exposure to blood and/or other body fluids that might contain HIV. It is imperative to follow universal precautions strictly, and consider all patients to be potentially infectious.

Who is Eligible for PEP? 37

- PEP should be offered, and initiated as early as possible, to all individuals with exposure that has the potential for HIV transmission, and ideally within 72 hours. a

- Assessment for eligibility should be based on the HIV status of the source whenever possible and may include consideration of background prevalence and local epidemiological patterns. b

- Exposures that may warrant PEP include the following:

- Parenteral or mucous membrane exposure (sexual exposure and splashes to the eye, nose or oral cavity).

- The following bodily fluids may pose a risk of HIV infection: blood, blood-stained saliva, breast-milk, genital secretions and cerebrospinal, amniotic, rectal, peritoneal, synovial, pericardial or pleural fluids. c

- Exposures that do not require PEP include the following:

- When the exposed individual is already HIV-positive.

- When the source is established to be HIV negative.

- Exposure to bodily fluids that does not pose a significant risk: tears, non-blood-stained saliva, urine and sweat.

a Although PEP is ideally provided within 72 hours of exposure, people may not be able to access services within this time. Providers should consider the range of other essential interventions and referrals that should be offered to clients presenting after the 72 hours.

b In some settings with high background HIV prevalence or where the source is known to be at high risk for HIV infection, all exposure may be considered for PEP without risk assessment.

c These fluids carry a high risk of HIV infection, but this list is not exhaustive and all cases should be assessed clinically and decisions made by the health-care workers as to whether exposure constitutes significant risk.

Knowing the HIV Status

Exposed Person37

- HIV testing in the context of PEP should include initial testing of the exposed individual with rapid diagnostic tests that can provide definitive results in most cases within 2 hours and often within 20 minutes.

- If the exposed person is already HIV positive – PEP is not indicated and appropriate ARV treatment intervention need to be given as per national ART guidelines.

- In emergency situations where HIV testing and counselling is not readily available but the potential HIV risk is high or if the exposed person refuses initial testing, PEP should be initiated and HIV testing and counselling undertaken as soon as possible.

Source Patient: 37, 38

- Whenever possible, the HIV status of the exposure source patient should be determined to guide appropriate use of HIV PEP.

- Administration of PEP should not be delayed while waiting for test results.

- If the source patient is determined to be HIV-negative:

- PEP should be discontinued, and no follow-up HIV testing for the exposed provider is indicated.

- If the source patient is determined to be HIV-positive the appropriate treatment and care needs to be given.

Timing and Duration of PEP:38

- Occupational exposures to HIV should be considered urgent medical concerns and treated immediately.

- PEP should be initiated as soon as possible:

- Preferably within 72 hours of exposure and

- Should be continued for a 4-week duration (28-day course)

- If the HIV status of a source patient for whom the practitioner has a reasonable suspicion of HIV infection is

unknown and the practitioner anticipates that hours or days may be required to resolve this issue:

- ARV medications should be started immediately rather than delayed.

Prescribing and dispensing PEP:37

- PEP can be initiated or dispensed by trained nonphysicians, midwives, nurses and other non-clinical health providers.

- Verbal consent is required.

- Individuals should be made aware of the risks and benefits of PEP, including information on potential drug–drug interactions and possible side effects and toxicity.

- Promoting adherence is critical to improving completion rates.

Recommendations for HIV PEP regimens in Adults and Adolescents

A regimen for PEP for HIV with two ARV drugs is effective, but three drugs are preferred.

The drug regimen selected for HIV PEP should have a favourable side effect profile, as well as a convenient dosing schedule to facilitate both adherence to the regimen and completion of 4 weeks of PEP.

|

|

WHO (adults and adolescents)31 |

CDC (Health Care Personnel)38 |

|

Preferred PEP Regimen |

TDF + 3TC (or FTC) and LPV/r or ATV/r |

TDF/FTC + RAL |

|

Alternative PEP Regimen |

TDF + 3TC (or FTC) along with anyone of RAL, DRV/r or EFV |

TDF + 3TC (or FTC) or AZT + 3TC (or FTC) along with anyone of RAL, DRV/r, ETR, RPV, ATV/r, LPV/r |

|

TDF - Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, 3TC - Lamivudine, FTC - Emtricitabine, RAL- Raltegravir, LPV/r - Lopinavir/ritonavir, AZT- Zidovudine, DRV/r - Darunavir/ritonavir, RPV -Rilpivirine, ETR- Etravirine |

||

The US Public Health Service guideline for occupational exposure mentions that the other ARVs that can be given as PEP, Only with Expert Consultation are abacavir (ABC), Efavirenz (EFV), Enfuvirtide (T20), Fosamprenavir (FOSAPV), Maraviroc (MVC), Saquinavir (SQV) and Stavudine (d4T).38

Certain ARVs are generally Not Recommended for use as PEP such as didanosine (ddI), nelfinavir (NFV) and tipranavir (TPV) while nevirapine (NVP) is contraindicated as PEP.38

The WHO PEP ARV regimens – children (≤10 years old):37

-

-

- In children, AZT + 3TC is the preferred backbone regimen.

- ABC + 3TC or TDF + 3TC (or FTC) can be considered as alternative regimens.

- LPV/r is recommended as the preferred third drug.

- An alternative third agent (age-appropriate) can be identified among ATV/r, RAL, DRV, EFV and NVP.

-

Situations for Which Expert Consultation for HIV PEP is Recommended38

- Delayed (i.e., later than 72 hours) exposure report

- Interval after which benefits from PEP are undefined

- Unknown source (eg. needle in sharps disposal container or laundry)

- Use of PEP to be decided on a case-by-case basis

- Consider severity of exposure and epidemiologic likelihood of HIV exposure

- Do not test needles or other sharp instruments for HIV

- Known or suspected pregnancy in the exposed person

- Provision of PEP should not be delayed while awaiting expert consultation

- Breast-feeding in the exposed person

- Provision of PEP should not be delayed while awaiting expert consultation

- Known or suspected resistance of the source virus to antiretroviral agents

- If source person’s virus is known or suspected to be resistant to 1 or more of the considered for PEP, selection of drugs to which the source person’s virus is unlikely to be resistant is recommended

- Do not delay initiation of PEP while awaiting any results of resistance testing of the source person’s virus

- Toxicity of the initial PEP regimen

- Symptoms (eg. gastrointestinal symptoms and others) are often manageable without changing PEP regimen by prescribing antimotility or antiemetic agents.

- Counseling and support for management of side effects is very important, as symptoms are often exacerbated by anxiety

- Serious medical illness in the exposed person

- Significant underlying illness (eg. renal disease) or an exposed provider already taking multiple medications may increase the risk of drug toxicity and drug-drug interactions

A close follow-up for exposed personnel should be provided that includes counselling, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and monitoring for drug toxicity; follow-up appointments should begin within 72 hours of an HIV exposure.

ARV-based Multipurpose Prevention Technologies (MPTs)

Female condoms have been marketed as an alternative barrier method, but this device, like the male condom, also requires acceptance by the male partner. In this context, prevention options that can be used and controlled by women to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV would be useful.39

MPTs aim to combine HIV prevention with prevention of unintended pregnancy and/or prevention/treatment of other STIs and reproductive tract infection.40

MPTs are multi-indication products, comprising either (1) multiple active agents, each individually effective for a different indication; (2) a single active agent effective for multiple indications (e.g. a single active drug with both microbicidal and contraceptive properties); or (3) one or more active agents incorporated into a medical device (e.g. a microbicide-releasing condom or diaphragm).40

Microbicides

Microbicides are chemical products that are self-administered prophylactic agents that can be applied topically in the vagina or rectum as a single agent or multi-component strategy.39 Candidate microbicides have been developed for delivery through various means, including gels, creams, tablets, films, slow-release, vaginal rings etc.3

Microbicide products are being developed for use vaginally or rectally to prevent sexual transmission of HIV-1. Vaginal microbicides offer a potentially important new prevention option for women.3

1% Tenofovir Gel

- The CAPRISA 004 trial assessed the effectiveness and safety of a 1% vaginal gel formulation of tenofovir for the prevention of HIV acquisition in women in 889 South African women. The study showed that tenofovir gel reduced HIV acquisition by an estimated 39% overall, and by 54% in women with high gel adherence. Women in the trial were counselled to use the gel within 12 hours before and after sex, a regimen known as BAT-24.41

- The VOICE trial in 5,029 African women in South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe was designed to test daily use of both oral (pill form) or topical (gel form) tenofovir-based prevention. It found that none of the interventions tested—daily oral TDF, daily oral TDF/FTC and daily tenofovir gel—reduced the risk of HIV prevention. Analyses showed that the participants were not using the interventions regularly enough to have detectable drug levels in their blood. This suggests that they did not follow the daily regimen as prescribed.42

- FACTS 001 was a Phase III, randomized, controlled trial, involving multiple South African research centres, that was set up to assess the safety and effectiveness of the vaginal microbicide, tenofovir gel, in preventing HIV infection in sexually active HIV-negative women aged 18 to 30 years. The outcome of this study showed that pericoital vaginal tenofovir 1% gel was not effective in preventing HIV acquisition. There was an association between adherence based on returned applicators and HIV effectiveness, and a significant association between tenofovir levels in cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) and reduction in HIV incidence.43

- MTN 017 is the first-ever expanded safety study (Phase II trial) of a rectal microbicide candidate, a reformulated version of tenofovir gel. It began in late 2013. It enrolled 186 men who have sex with men at sites in Peru, South Africa, Thailand and the United States. In each 8 week study period participants were randomized to reduced glycerine (RG)-TDF rectal gel daily; or RG-TDF rectal gel before and after receptive anal intercourse (RAI) (or at least twice weekly in the event of no RAI); or took daily oral FTC/TDF. Participants were seen every 4 weeks. The study found that reduced glycerin tenofovir gel was safe. Participants were equally adherent to using gel before and after sex (93%) as they were to taking daily TDF/FTC 94%. They were less adherent to using gel on daily basis 83%.44,45,46

Vaginal Rings: Dapivirine Ring

Vaginal rings are flexible, torus-shaped, silicone elastomer or thermoplastic devices that provide long-term, sustained or controlled delivery of pharmaceutical substances to the vagina for either local or systemic effect. They are generally positioned in the upper third of the vagina adjacent to the cervix, to be readily inserted and removed by the woman herself.3

The dapivirine ring is being tested for its ability to reduce the risk of HIV infection. It slowly releases the ARV dapivirine. A new ring has to be inserted every 4 weeks to maintain drug delivery. Two trials evaluated whether the ring is safe and effective at reducing the risk of HIV infection.3,44

- ASPIRE (MTN 020) was launched by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) in 2012 and enrolled 2,629 HIV-infected women aged 18–45 years in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe. The ring was to be used for a period of four weeks and then replaced by another. The ring was impregnated with 25 milligrams (mg) of dapivirine. Dapivirine ring reduced the risk of acquiring HIV by 27% among women enrolled in the study.47

- The Ring Study (IPM 027) is sponsored by the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM) and is enrolling 1,950 women aged 18–45 years at sites in Uganda and South Africa. The dapivirine ring reduced the risk of HIV infection by 31%.48

In the new analysis announced by MTN at AIDS 2016 in Durban, researchers found that, among women who appeared to use the monthly ring consistently, HIV risk was cut by at least 56% — a statistically significant finding. Additional subgroup analyses of women who appeared to use the ring the most suggested that the product reduced HIV risk by 75% or more.49

A Phase 2a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the dapivirine ring was conducted in sexually active females, aged 15-17 years across six cities in the US. 96 participants were randomized (3:1) to receive dapivirine or placebo ring that was to be inserted monthly for 6 months. A plasma dapivirine concentration >95 pg/mL was used to define short- term adherence (hours; a dapivirine residual level <23.5 mg was used to define long-term adherence (monthly). In the dapivirine group, drug levels indicated adherence in 87% of plasma samples and 95% of rings. Participants noted no discomfort due to the ring at 87% of visits and “liking” the ring at 93% of visits. The dapivirine vaginal ring, was reported to be a promising microbicide approach, and was safe and acceptable in this population.50

The Future for the Ring49

Based on results from The Ring Study and ASPIRE, and anchored by the new data presented at AIDS 2016, the International Partnership for Microbicides’ plans to launch DREAM and HOPE open-label extension ‘follow-on’ studies. The studies will offer the active dapivirine ring to HIV-negative women who participated in The Ring Study and ASPIRE, respectively, and collect additional data on safety.

Other Non-ARV based Strategies for HIV Prevention

Although ART has a significant HIV prevention effect, it should be used in combination with other biomedical interventions that reduce HIV risk practices and/or reduce the probability of HIV transmission per contact event, including male and female condoms, needle and syringe programmes, opioid substitution therapy with methadone or buprenorphine and voluntary medical male circumcision.32

Medical Male Circumcision

Male circumcision is one of the oldest and most common surgical procedure performed on newborns and young boys for nonmedical reasons and was first proposed as an HIV-prevention intervention for men over a decade ago, based on observational data.51

Male circumcision is surgical removal of the foreskin – the retractable fold of tissue that covers the head of the penis. The inner aspect of the foreskin is highly susceptible to HIV infections. Trained health professionals can safely remove the foreskin of infants, adolescents and adults (medical male circumcision).52

Circumcision is known to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition among men. There could be many reasons as to how this could occur. The foreskin has a tendency to develop epithelial disruptions, or tears, during intercourse, which may allow HIV a portal of entry, and compared with the tissue of the outer foreskin, the foreskin’s HIV target cells (Langerhans cells with CD4 receptors) are closer to the epithelial surface.52

The programmatic implementation of adult Medical Male Circumcision (MMC) in several Sub-Saharan African countries could, in 10 years, reduce HIV acquisition in men by at least 60%.53 It was observations from these three trials, i.e. Kisumu (Kenya), Rakai District (Uganda) and South Africa Orange Farm Intervention Trial, which demonstrated at least a 60% reduction in HIV infection among men who were circumcised.54

Nearly 15 million voluntary medical male circumcisions (VMMC) have been performed for HIV prevention in 14 countries of eastern and southern Africa during the decade since WHO and UNAIDS recommended (2007) VMMC as an additional HIV prevention intervention. In 2016, 2.8 million VMMCs were performed as represented in figure 5. From 2015 to 2016, the number of VMMCs performed increased by nearly 9%. The majority of VMMC clients were aged 15 years or older. Impressive scale-up has taken place, approaching the global 2016 target (set in 2011) of 20.8 million as shown in figure 6.55

Annual number of medical male circumcisions performed in 14 priority countries in East and Southern Africa, 2008–201644

The WHO has laid down certain guidelines recommending the use of VMMC and its implementation in targeted key population groups. Following are the WHO 2016 recommendations for the use of VMMC 32

- All key population groups

- VMMC is recommended as an additional, important strategy for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men, particularly in settings with hyperendemic and generalized HIV epidemics and low prevalence of male circumcision.

- VMMC service provision should serve as an opportunity to address the sexual health needs of men; such services should actively counsel and promote safer sexual behaviour.

- MSM

- Due to lack of evidence of VMMC during receptive anal intercourse, it is not recommended to prevent HIV transmission in sex between men.

- MSM may still benefit from VMMC if they also engage in vaginal sex.

- In eastern and southern Africa where VMMC is offered for HIV prevention, MSM should not be excluded from VMMC services.

- People in prisons and other closed settings

- VMMC is not one of the recommended interventions in the prison package.

- Sex workers (and clients of sex workers)

- Health messages and counselling should emphasize that resuming sexual relations before complete wound healing may increase the risk of HIV acquisition among recently circumcised HIV-negative men and may increase the risk of HIV transmission to female partners of recently circumcised HIV-positive men.

- “Men’s health services” offering VMMC to clients of sex workers or other men at higher risk (such as in serodiscordant couples) may be a promising approach in the high-priority countries of eastern and southern Africa to reach men at greater risk of HIV infection. This approach has not been systematically reviewed and evaluated.

- Transgender people

- VMMC is not recommended for HIV prevention among TGW.

- Adolescents from key populations

- Countries with hyperendemic and generalized HIV epidemics and low prevalence of male circumcision should increase access to male circumcision services as a priority for adolescents and young men.

VMMC devices for adults and adolescents3

|

Type |

Summary characteristics |

Example |

|

Surgical-assist male circumcision devices |

Reusable metal or single-use disposable plastic devices employed during surgery and not worn by the client after the procedure. |

Unicirc Simple Circ |

|

Clamp and latch male circumcision devices |

Disposable devices that use a clamping mechanism to hold the device in place and control bleeding at the site of incision and that are worn for about seven days after device placement and foreskin removal. |

Shang Ring Tara KLamp Ali’s Klamp Smartklamp |

|

Male circumcision devices with ligature compression |

Disposable devices that use a ligature to hold the device in place for about seven days and control bleeding at the incision after device placement and foreskin removal. |

Zhenxi Ring |

|

Male circumcision devices with elastic collar compression |

Disposable devices that use an elastic ring to induce necrosis of the intact foreskin. The device and necrotic foreskin are removed at the same time, about seven days after placement. |

PrePex |

In a WHO meeting held in Entebbe, Uganda, (November 2013), an analysis was conducted comparing surgical methods to male circumcision devices. The outcome of the analysis was based on a total of 1983 ShangRing and 2,417 PrePex procedures.56

It was observed that men reported a high level of satisfaction with the cosmetic result following both types of circumcision – device and conventional surgery. However, a larger proportion of physicians and non-physicians expressed a preference for a device over conventional surgical circumcision.56

Common advantages reported by providers with the device techniques compared to the conventional procedure were as below.56

- Easy to perform and faster

- Better cosmetic results

- Fewer complications

- Remove the need for suturing

- Cause less bleeding,

- Remove the need for routine injectable anaesthesia (in the case of the PrePex)

Therefore, VMMC is an important preventive strategy. However, it provides only partial protection and, therefore, should be only one element of a comprehensive HIV prevention package, which includes the following: the provision of HIV testing and counselling services; treatment for STIs; the promotion of safer sex practices; and, the provision of male and female condoms and promotion of their correct and consistent use.57

Condoms and Lubricants

ARV-based treatment and prevention options appear promising in controlling the disease progression and transmission. However, barrier methods still remain an important part of the comprehensive prevention package.

Condoms are an essential component of comprehensive efforts to control the HIV epidemic, both for those who know their status and for those who do not.58 Consistent and correct use of male condoms reduces sexual transmission of HIV and other STIs in both vaginal and anal sex by up to 94%.32 Male condoms are highly effective in preventing HIV transmission and female condoms have similar efficacy as the male condoms, but are 20 times more expensive.32

Use of water- or silicone-based lubricants (as opposed to petroleum-based) helps to prevent condoms from breaking and slipping. While fewer data are available on female condoms, evidence suggests that the use of female condoms also prevents HIV and STIs.32

WHO 2016 Recommendations32

In all key population groups the correct and consistent use of condoms with condom-compatible lubricants is recommended for all key populations to prevent sexual transmission of HIV and STIs.

The WHO emphasizes on the need to enforce and promote the use of condoms. Male and female condoms should be made easily available and accessible. Condom promotion campaigns should increase awareness, promote the acceptability and benefits of condom use, and help to overcome social and personal obstacles to their use.

Conclusion

The recent epidemiological update by the UNAIDS shows that efforts taken worldwide have successfully contributed towards curbing the epidemic of HIV/AIDS. Up to 19.5 million HIV-infected individuals are receiving ARV treatment as of 2016.1 The decline in the incidence of HIV is accelerating and prevention strategies will only enhance this success. Unless the number of new infections falls sharply, long-term costs associated with the provision of lifelong ART in low- and middle-income countries could soon become prohibitive, potentially threatening advances achieved to date by the global AIDS response.3

Along with use of ARVs as prevention, other HIV prevention technologies are also being developed and likely to emerge in the foreseeable future. Continuous research and efforts are underway to develop these HIV prevention tools. The use of ART will need to be part of a combination prevention strategy to achieve successful outcomes. Therefore, with the newer technologies available for HIV prevention and those that will become available from ongoing research, the spread of HIV can be expected to be controlled.59

References

1. Global AIDS Update. UNAIDS 2016

2. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/2017_data_book

Last accessed 16th November 2017

3. HIV Preventives Technology and Market Landscape; 2nd Edition; 2014

4. Terris-Prestholt F, Hanson K, MacPhail C et al. How much demand for New HIV prevention technologies can we really expect? Results from a discrete choice experiment in South Africa PLoS One. 2013 Dec 30;8(12):e83193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083193. eCollection 2013.

5. http://www.thebody.com/content/75211/how-can-i-prevent-hiv-transmission-infographic.html Last accessed 16th November 2017

6. Bisrat K. A, Roy G. Next Generation Oral PrEP: Beyond Tenofovir Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012 Nov; 7(6): 600–606.

7. http://www.aidsmap.com/PrEP-use-in-US-exceeds-100000-in-Gilead-pharmacy-survey/page/3165157/Last Accessed 13th November 2017

8. http://www.prepwatch.org/advocacy/country-updates/ Last accessed 16th November 2017

9. Guideline on When To Start Antiretroviral Therapy And On Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis For HIV; WHO 201F5, http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prep/prep-implementation-tool/en/ Last Accessed 17th November 2017

10. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States – 2014 Clinical Practice Guideline; CDC 2014

11. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2587-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205.

12. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):399-410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524.

13. Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):423-34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711.

14. Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013 Jun 15;381(9883):2083-90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7.

15. McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016 Jan 2;387(10013):53-60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. and CROI, 2015. Abstract 22LB

16. Hosek SG, Landovitz RJ, Kapogiannis B et al. Safety and Feasibility of Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis for Adolescent Men Who Have Sex With Men Aged 15 to 17 Years in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Nov 1;171(11):1063-1071. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2007

17. CROI, 2015. Abstract 23LB, and Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B et al. On-Demand Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men at High Risk for HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 3;373(23):2237-46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506273.

18. IAS 2015; Abstracts MOAC0306LB, MOAC0305LB and MOSY0103 and

19. Technical update on Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP); WHO 2015

20. IAS 2015; Abstract TUAC0202

21. García-Lerma JG, Paxton L, Kilmarx PH et al. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010 Feb;31(2):74-81. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.10.009.

22. Hiremath R, Kamble M, Bhalla S et at. Zero transmission of HIV– “Still a long way to go” An Update on TasP: PrEP and PEP of HIV infection. IJBAR 2014; 05 (07). doi:10.7439/ijbar

23. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11;365(6):493-505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243.

24. http://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/hiv-study-named-2011-breakthrough-year-science Last accessed on 17th November 2017

25. IAS 2011; Oral Abstract MOAX0102

26. IAS 2015; Abstract MOAC0101LB

27. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents; DHHS 2016

28. BHIVA guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1 positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2015; BHIVA 2015

29. European AIDS Clinical Society guidelines, Version 8.2; EACS 2017

30. Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA et al. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2016 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2016 Jul 12;316(2):191-210. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8900.

31. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach; WHO 2016 2nd Edition

32. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations WHO 2016

33. http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/mtct/en/ Last accessed on 17th November 2017

34. Kim MH, Ahmed S, Hosseinipour MC, et al. Implementation and operational research: the impact of option B+ on the antenatal PMTCT cascade in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 Apr 15;68(5):e77-83. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000517.

35. https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/malawi

Last Accessed 16th November 2017

36. Sultan B, Benn P, Waters L et al. Current perspectives in HIV post-exposure prophylaxis. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2014 Oct 24;6:147-58. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S46585.

37. Guidelines On Post-Exposure Prophylaxis For HIV And The Use Of Co-Trimoxazole Prophylaxis For HIV-Related Infections Among Adults, Adolescents And Children: Recommendations For A Public Health Approach; WHO 2014

38. Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA et al. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013 Sep;34(9):875-92. doi: 10.1086/672271.

39. Abdool Karim S. S. and Baxter C. Overview of Microbicides for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 Aug; 26(4): 427–439.

40. Malcolm RK, Boyd P, McCoy CF et al. Beyond HIV microbicides: multipurpose prevention technology products. BJOG. 2014 Oct;121 Suppl 5:62-9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12852.

41. Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010 Sep 3;329(5996):1168-74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. Epub 2010 Jul 19

42. Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 5;372(6):509-18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269

43. CROI, 2015. Abstract 26LB

44. Prevention on the line; AVAC report 2014-15

45. http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/news/studies/mtn017/qa Last accessed 17th November 2017

46. CROI, 2016. Abstract 108LB

47. CROI, 2016. Abstract 109LB

48. CROI, 2016. Abstract 110LB

49. http://www.ipmglobal.org/content/ipms-dapivirine-ring-may-offer-significant-hiv-protection-when-used-consistently-new-data Last Accessed 17th November 2017

50. 9th IAS Conference on HIV Science 23-26 July 2017, Paris, France Abstract TUAC0206LB

51. Justman J, Goldberg A, Reed J et al. Adult male circumcision: reflections on successes and challenges. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 Jul;63 Suppl 2:S140-3. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829875cc.

52. Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention; WHO factsheet 2012

53. Weiss SM, Zulu R Jones D et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial to increase the availability and acceptability of voluntary medical male circumcision in Zambia: The Spear and Shield Project. Lancet HIV. 2015 May 1; 2(5): e181–e189.

54. New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications; UNAIDS 2007

55. WHO Progress Brief - Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in 14 priority countries of East and Southern Africa;July 2017

56. Use of Devices for Adult Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention in East and Southern Africa. Meeting report. 13–14 November 2013, Entebbe, Uganda

57. www.who.int/hiv/topics/malecircumcision/en/ Last accessed 17th November 2017

58. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV Transmission (Review); the Cochrane Library (4) 2007.

59. AIDS. 2012 Aug 24;26(13):1585-98

List of Abbreviations

3TC: Lamivudine

ABC: Abacavir

AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

ART: Antiretroviral Therapy

ARV: Antiretroviral

ATV/r: Atazanavir/ ritonavir

AZT: Zidovudine

DRV/r: Darunavir/ ritonavir

DTG: Dolutegravir

EFV: Efavirenz

FTC: Emtricitabine

HAART-Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

INSTI: Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor

LPV/r: Lopinavir/ ritonavir

MPTs- Multipurpose Prevention Technologies

MSM- Men who have Sex with Men

MTCT: Mother-to-Child Transmission

NNRTI: Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor

NRTI: Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor

NVP: Nevirapine

PEP- Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

PI: Protease Inhibitor

PMTCT: Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission

PrEP – Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

RAL: Raltegravir

RTV: Ritonavir

TasP- Treatment as Prevention

TDF: Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate

TG- TransGender

TGW- Transgender Women

UNAIDS-The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS

USFDA: United States Food and Drug Administration

WHO: World Health Organization